Users Do Things

This chapter introduces the concept of a Task Based User Interface and compares it with a CRUD style user interface. It also shows the changes that occur within the Application Server when a more task oriented style is applied to it’s API.

One of the largest problems seen in “A Stereotypical Architecture” was that the intent of the user was lost. Because the client interacted by posting data-centric DTOs back and forth with the Application Server, the domain was unable to have any verbs in it. The domain had become a glorified abstraction of the data model. There were no behaviors, the behaviors that existed, existed in the client, on pieces of paper, or in the heads of the users of the software.

Many examples of such applications can be cited. Users have “work flow” information documented for them. Go to screen xyz edit foo to bar, then go to this other screen and edit xyz to abc. For many types of systems this type of workflow is fine. These systems are also generally low value in terms of the business. In an area that is sufficiently complex and high enough ROI in order to use Domain Driven Design these types of workflows become unwieldy.

One reason that is commonly cited for wanting to build a system such as described is that “the business logic and work flows can be changed at any time to anything without need of a change to the software”. While this may be true it must be asked at what cost. What happens when someone misses a step in the process they have in their head or you have multiple users who do it differently as is commonly the case? How do you get any reasonable information out of a system in terms of reporting?

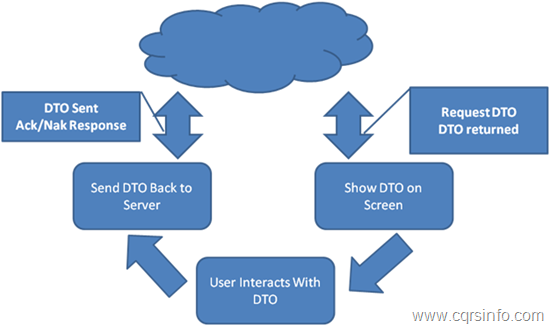

One way of dealing with this issue is to move away from the DTO up/down architecture that was illustrated in a “Stereotypical Architecture”. Figure 1 shows the client interaction side of a DTO up/down architecture.

Figure 1 Interaction in a DTO Up/Down Architecture

The basic explanation of the operation is that the UI will request a DTO, say for Customer 1234 from the Application Server. This DTO will be returned to the client and then shown on the screen. The user will interact with the DTO in some way (likely either directly or through a View Model). Eventually the client will click Save or some other trigger will occur and the client will take the DTO and send it back up to the Application Server. The Application Server will then internally map the data back to the domain model and save the changes returning a success or failure.

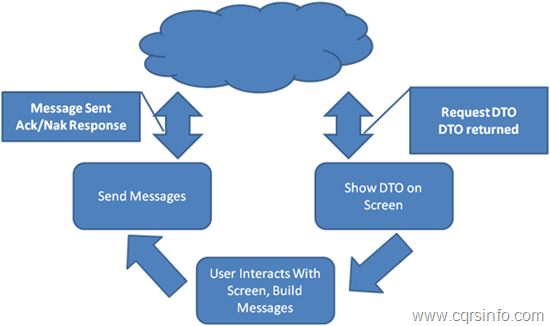

As discussed the intention of the user is being lost because a DTO is being sent up that just represents the current state of the object after the client’s actions are completed. It is possible to bring forward the intention of the user; this will allow the Application Server to process behaviors as opposed to saving data. Figure shows an interaction capturing intent.

Figure 2 Behavioral Interface

Capturing intent the client interaction is very similar to the DTO up/down methodology in terms of interactions. The client first quests a DTO from the Application Server for instance Customer 1234. The Application Server returns a DTO representing the customer that is then shown on the screen for the user to interact with usually either directly or through a View Model. The similarities however stop at this point.

Instead of simply sending the same DTO back up when the user is completed with their action the client needs to send a message to the Application Server telling it to do something. It could be to “Complete a Sale”, “Approve a Purchase Order”, “Submit a Loan Application”. Said simply the client needs to send a message to the Application Server to have it complete the task that the user would like to complete. By telling the Application Server what the user would like to do, it is possible to know the intention of the user.

Commands

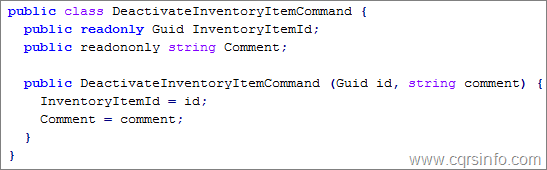

The method through which the Application Server will be told what to do is through the use of a Command. A command is a simple object with a name of an operation and the data required to perform that operation. Many think of Commands as being Serializable Method Calls. Listing 1 includes the code of a basic command.

Listing 1 A Simple Command

As a side note the example in Listing 1 includes the pattern name after the name of the Command. This is a decision that has many positives and negatives both linguistically and operationally. The choice over whether to use a pattern name in a class name is one that should not be taken lightly by a development team.

One important aspect of Commands is that they are always in the imperative tense; that is they are telling the Application Server to do something. The linguistics with Commands are important. A situation could for with a disconnected client where something has already happened such as a sale and could want to send up a “SaleOccurred” Command object. When analyzing this, is the domain allowed to say no that this thing did not happen? Placing Commands in the imperative tense linguistically shows that the Application Server is allowed to reject the Command, if it were not allowed to, it would be an Event for more information on this see “Events”.

Occasionally there exist funny examples of language in English. A perfect example of this would be “Purchase” which can be used either as a verb in the imperative or as a noun describing the result of its usage in the imperative. When dealing with these situations, ensure that the concept being pushed forward represents the imperative of the verb and not the noun. As an example a purchase should be including what to purchase and expecting the domain to possibly fill in some information like when the item was purchased as opposed to sending up a purchase DTO that fully describes the purchase.

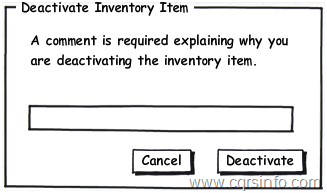

The simple Command in Listing 1 includes two data properties. It includes an Id which represents the InventoryItem it will apply to and it includes a comment as to why the item is being deactivated. The comment is quite typical of an attribute associated with a Command, it is a piece of data that is required in order to process the behavior. There should only exist on a Command data points that are required to process the given behavior. This contrasts greatly with the typical architecture where the entire data of the object is passed back to the Application Server.

Most importantly of the data is the Id of the associated inventory item. At least one Id must exist for all commands that are updating state in some way, as all commands are intended to be routed to an object. When issuing a Create Command it is not necessary though valuable to include an Id. Having the client originate Ids normally in the form of UUIDs is extremely valuable in distributed systems.

It is quite common for developers to learn about Commands and to very quickly start creating Commands using vocabulary familiar to them such as “ChangeAddress”, “CreateUser”, or “DeleteClass”. This should be avoided as a default. Instead a team should be focused on what the use case really is.

Is it “ChangeAddress”? Is there a difference between “Correcting an Address” and “Relocating the Customer”? It likely will be if the domain in question is for a telephone company that sends the yellow pages to a customer when they move to a new location.

Is it “CreateUser” or is it “RegisterUser”? “DeleteClass” or “DeregisterStudent”. This process in naming can lead to great amounts of domain insight. To begin defining Commands, the best place to begin is in defining use cases, as generally a Command and a use case align.

It is also important to note that sometimes the only use case that exists for a portion of data is to “create”, “edit”, “update”, “change”, or “delete” it. All applications carry information that is simply supporting information. It is important though to not fall into the trap of mistaking places where there are use cases associated with intent for these CRUD only places.

Commands as a concept are not difficult but are different for many developers. Many developers see the creation of the Commands as a lot of work. If the creation of Commands is a bottleneck in the workflow, many of the ideas being discussed are likely being applied in an incorrect location.

User Interface

In order to build up Commands the User Interface will generally work a bit differently than in a DTO up/down system. Because the UI must build Command objects it needs to be designed in such a way that the user intent can be derived from the actions of the user.

The way to solve this is to lean more towards a “Task Based User Interface” also known as an “Inductive User Interface” in the Microsoft world. This style of UI is not by any means new and offers a quite different perspective on the design of user interfaces. Microsoft identified three major problems with Deductive UIs when researching Inductive UIs.

Users don’t seem to construct an adequate mental model of the product. The interface design for most current software products assumes that users will understand a conceptual model that the designers carefully crafted. Unfortunately, most users don’t seem to ever acquire a mental model that is thorough and accurate enough to guide their navigation. These users aren’t dumb — they are just very busy and overloaded with information. They do not have the time, energy, or desire to wonder about a conceptual model for their software.

Even many long-time users never master common procedures. Designers know that new users may have trouble at first, but expect these problems to vanish as users learn common tasks. Usability data indicates this often doesn’t happen. In one study, researchers set up automated equipment to videotape users at home. The tapes showed that users focusing on the task at hand do not necessarily notice the procedure they are following and do not learn from the experience. The next time users perform the same operation, they may stumble through it in exactly the same way.

Users must work hard to figure out each feature or screen. Most software products are designed for (the few) users who understand its conceptual model and have mastered common procedures. For the majority of customers, each feature or procedure is a frustrating, unwanted puzzle. Users might assume these puzzles are an unavoidable cost of using computers, but they would certainly be happier without this burden.

Microsoft Corporation, 2001

The basic idea behind a Task Based or Inductive UI is that its important to figure out how the users want to use the software and to make it guide them through those processes.

Many commercial software applications include user interfaces in which a screen presents a set of controls, but leaves it to the user to deduce the page’s purpose and how to use the controls to accomplish that purpose.

Microsoft Corporation, 2001

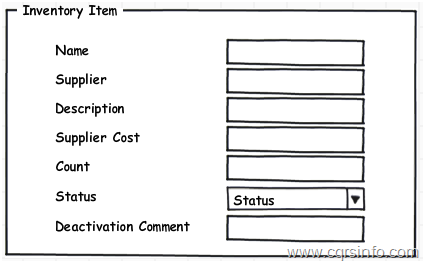

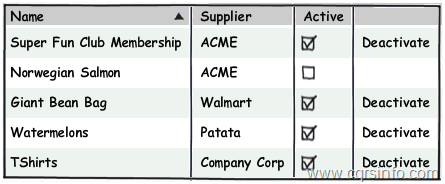

The goal is to guide the user through the process. An example of the differences can be seen in the DeactivateInventoryItem example previously shown. A typical deductive UI might have an editable data grid containing all of the inventory items. It would have editable fields for various data and perhaps a drop down for the status of the inventory item, deactivated being one of them. In order to deactivate an inventory item the user would have to go to the item in the grid, type in a comment as to why they were deactivating it and then change the drop down to the status of deactivated. A similar example could be where you click to a screen to edit an inventory item but go through the same process as seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3 A CRUD screen for an Inventory Item

If the user attempts to submit an item that is “deactivated” and has not entered a comment they will receive an error saying that they must enter a comment as it is a mandatory field for a deactivated item. Some UIs might be a bit more user friendly, they may not show the comment field until the user selects deactivated from the drop down at which point it would appear on the screen. This is far more intuitive to the user as it is a cue that they should be putting data in that field but one can do even better.

Figure 4 Listing Screen with Link

A Task Based UI would take a different approach, likely it would show a list of inventory items, next to an inventory item there might be a link to “deactivate” the item as seen in Figure 4. This link would take them to a screen that would then ask them for a comment as to why they are deactivating the items which is shown in Figure 5. The intent of the user is clear in this case and the software is guiding them through the process of deactivating an inventory item. It is also very easy to build Commands representing the user’s intentions with this style of interface.

Figure 5 Deactivating an Inventory Item

Web, Mobile, and especially Mac UIs have been trending towards the direction of being task based. The UI guides you through a process and offers you contextually sensitive guidance pushing you in the right direction. This is largely due to the style offering the capability of a much better user experience. There is a solid focus on how and why the user is using the software; the user’s experience becomes an integral part of the process. Beyond this there is also value on focusing more in general on how the user wants to use the software; this is a great first step in defining some of the verbs of the domain.

Works Cited

- Microsoft Corporation. (2001, Feb 9). Microsoft Inductive User Interface Guidelines. Retrieved from MSDN: http://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/ms997506

I discuss some of the other issues of not having task based UI here.

What if you want deactivate multiple items at once?

Greatings!

The task based interface should not show products with status not active. Right?

У вас хороший форум!

you don’t need to create a commands in most cases to follow those principles, functions\procedures should be enough

Новые бмв в России

Hi,

I can capture users intentions in my inductive UI. But I also need a way for user just to amend data in case he made an error. Typo or whatever. So I need to provide a simple edit functionality for him.

Once I do that, users can use that generic edit functionality to do their work without going through my inductive UI. So she has two ways now to achieve same thing. And that screws up my intention capturing architecture.

Any ideas?

Regards,

Sharas

Hi,

An useful way to think about ui for users.

But I am missing something. Asynchrony.

Using the CQRS paradigm, the command triggers a task on the server side which returns anything else than an ack/nack of the command. In my understanding, this should have an impact on the way of thinking the UI that can’t return the real result if the command. Right ?