In “Events as a Storage Mechanism” the concept of rebuilding state from a series of events was looked at from a conceptual viewpoint. This chapter will focus on the implementation of an actual Event Storage and some of the issues that come up in producing an implementation.

The implementation discussed in this chapter is not intended to be a production quality Event Storage, more so it is provided as a discussion point around how to build an Event Storage. The implementation here although not highly performant could meet the needs of a large percentage of applications that are built today.

For the explanatory implementation it is easiest to build the Event Storage in an existing technology such as a RDBMS. This will alleviate many of the technical issues that can arise that are out of the scope of a basic discussion on how to build an event storage such as transaction commit models or data locality for read performance.

Structure

A basic Event Storage can be represented in a Relational Database utilizing only two tables.

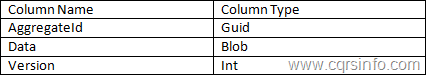

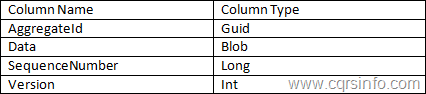

Figure 1 Table Layout for Events Table

This table represents the actual Event Log. There will be one entry per event in this table. The event itself is stored in the [Data] column. The event is stored using some form of serialization, for the rest of this discussion the mechanism will assumed to be built in serialization although the use of the memento pattern can be highly advantageous.

The table is shown with the minimum amount of information possible, most organizations would want to add a few columns such as the time that the change was made or context information associated with the change. Examples of context information might include the user that initiated the change, the ip address they sourced the change from, or their level of permission when they sourced the change.

A version number is also stored with each event in the Events Table. This can generally be thought of as an increasing integer for most cases. Each event that is saved has an incremented version number. The version number is unique and sequential only within the context of a given aggregate. This is because Aggregate Root boundaries are consistency boundaries.

The [AggregateId] column is a foreign key that should be indexed; it points to the next table which is the Aggregates table.

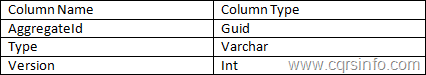

Figure 2 Table Layout for Aggregates Table

Author comment: I have gone back and forth between calling this concept “Aggregate” in the Event Storage in lieu of another name such as “Event Provider” as “Aggregate” is really a domain concept and an Event Storage could work without a domain.

The Aggregates table is representing the aggregates currently in the system, every aggregate must have an entry in this table. Along with the identifier there is a denormalization of the current version number. This is primarily an optimization as it could be derived from the Events table but it is much faster to query the denormalization that it would be to query the Events table directly. This value is also used in the optimistic concurrency check.

Also included is a [Type] column for this example, this would be the fully qualified name of the type of aggregate being stored. This can be useful for various purposes not the least of which is debugging, it is however unnecessary for the creation of a basic Event Storage.

Operations

Event Storages are far simpler that most data storage mechanisms as they do not support general purpose querying. An Event Storage at its simplest level has only two operations. Having only two operations makes an Event Storage simpler than most data storage mechanisms as well as easier to optimize.

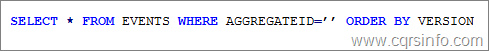

The first operation is to get all of the events for an aggregate. It is extremely important that the events are ordered in the same order that they were written, the version number can be used for this purpose. This can all be done quite simply using an underlying RDBMS.

This is the only query that should be executed by a production system against the Event Storage. A possible secondary query that can be useful is to limit this result set by an actual date to see the state of an object at a point in time, but generally a production system should not be doing this.

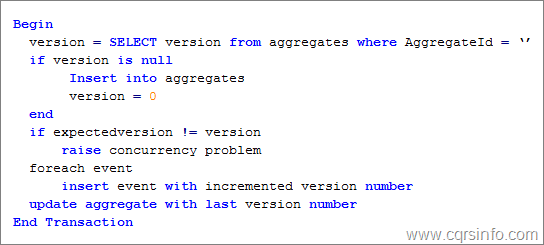

The other operation an Event Storage must support is the writing of a set of events to an aggregate root. This can be done either in code or in a stored procedure. A stored procedure or dynamically generated SQL containing if statements is preferred as without the insert process will take multiple round trips. The pseudo-code for the insert process can be seen in Listing 1.

Listing 1 Write Operation in Event Storage

The write operation is also relatively simple though there are a few subtleties to be found within it. The basic narrative is that it first checks to see if an aggregate exists with the unique identifier it is to use, if there is not one it will create it and consider the current version to be zero. It will then attempt to do an optimistic concurrency test on the data coming in if the expected version does not match the actual version it will raise a concurrency exception. Providing the versions are the same, it will then loop through the events being saved and insert them into the events table, incrementing the version number by one for each event. Finally it will update the Aggregates table to the new current version number for the aggregate. It is important to note that these operations are in a transaction as it is required to insure that optimistic concurrency amongst other things works in a distributed environment.

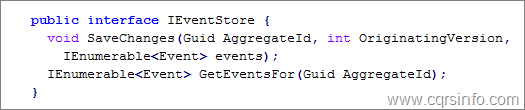

The contract for an Event Storage in code can be defined with the following interface.

Listing 2 Interface for an Event Store

Although not a trivial exercise to create a production quality Event Storage the overall concepts behind an Event Storage are relatively easy. Likely in the future there will be many off the shelf Event Storage systems available as either products or open source projects. There is however one very important optimization that was discussed in “Events as a Storage Mechanism” that really should exist in most systems and that is the concept of a “Rolling Snapshot”.

Rolling Snapshots

Rolling Snapshots are a heuristic to prevent the need to load all of the events when issuing a query to rebuild an Aggregate. They are a denormalization of the aggregate at a given point in time. A change to the query logic and an additional table are all that is necessary to add the heuristic to the basic Event Storage. Further discussion on Rolling Snapshots at a conceptual level can be found in the “Events as a Storage Mechanism” chapter.

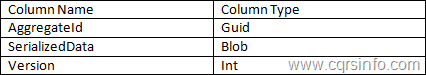

Figure 3 Definition of Snapshots Table

The Snapshots table is relatively basic. It’s primary data in the blob that contains the serialized version of the aggregate at a given point in time. The serialized data could be in any one of a host of possible schemas, binary, XML, raw text, etc. The decision on how to serialize the snapshots is really dependent upon the system being built. A version number is included with the snapshot, it represents which version of the aggregate the snapshot represents.

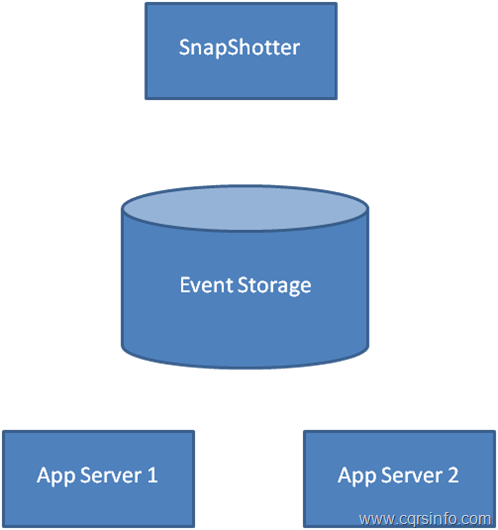

In order to have snapshots being created a process that handles the task of creating the snapshots needs to be introduced. This process can live outside of the Application Server as a background process. There can be a single process running or many depending on needs due to throughput. All snapshots happen asynchronously. Figure 4 shows a conceptual architecture with a [SnapShotter] process introduced.

Figure 4 Introduction of a Snapshotter

The [SnapShotter] sits behind the Event Storage and periodically queries for any Aggregates that need to have a snapshot taken because they have gone past the allowed number of events. This query can be done quite easily in the simple Event Storage discussed by joining the Aggregates table to the Snapshots table on the Aggregate identifier. The difference is calculated by subtracting the last snapshot version from the current version with a where clause that only returned the aggregates with a difference greater than some number. This query will return all of the Aggregates that a snapshot to be created. The snapshotter would then iterate through this list of Aggregates to create the snapshots (if using multiple snapshotters the competing consumer pattern works well here).

The process of creating a snapshot involves having the domain load up the current version of the Aggregate then take a snapshot of it. The creation of the snapshot can be done in many ways. Once the snapshot has been taken, it is saved back to the snapshot table so that queries will have the snapshot available.

Many use the default serialization package available with their platform with good results though the Memento pattern is quite useful when dealing with snapshots. The Memento pattern (or custom serialization) better insulates the domain over time as the structure of the domain objects change. The default serializer has versioning problems when the new structure is released (the existing snapshots must either deleted and recreated or updated to match the new schema). The use of the Memento pattern allows the separated versioning of the snapshot schema from the domain object itself.

In “Events as a Storage Mechanism” a different, simpler mechanism was shown for the storage of snapshots. That system had the snapshots in line in the Event Log, this other mechanism although conceptually simpler has a few issues that can come up in a production system. The issues revolve around the need of ordering of the snapshot within the event log.

Consider that the Snapshotter has realized that an Aggregate Root needs to have a snapshot taken. It loads up the Aggregate and takes the snapshot. Unfortunately while it was doing this, one of the Application Servers made a change to the same Aggregate. As the snapshot is position dependent within the Event Log, it would receive an optimistic concurrency failure. The easy answer would be to simply repeat the process but what if it failed again? The snapshotter on a very busy Aggregate could end up in a situation where it would have a very low probability of actually writing the snapshot successfully.

By separating the snapshots into their own table and associating them to a version of the aggregate this problem is solved. Ordering of snapshots is not needed, the snapshot does not even need to be at the latest version, the snapshot that is taken is valid at the version it was taken.

Snapshots are a heuristic that will dramatically improve the performance of many systems, though not all systems need snapshotting. It is generally recommended to handle development without snapshotting as it can always be introduced later as a simple performance enhancement for the system.

Event Storage as a Queue

It has been previously discussed that the events coming out of a domain are also an [Integration Model]. Very often these events are not only saved but also published to queue where they are dispatched asynchronously to listeners either within the same system (the reporting model is a good example) or to other applications. An issue that exists with many systems publishing events is that they require a two-phase commit between whatever storage they are using (Relational or otherwise) and the publishing of their events to the queue.

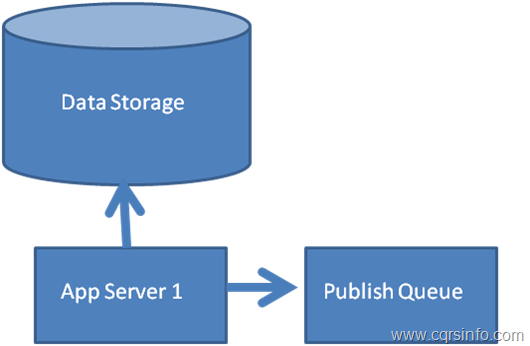

The reason that the two-phase commit is needed is that a catastrophe could occur during the small period of time between when the write to the data storage commits and when the write to the queue commits. If a failure were to happen during this period the message would not be published on the queue (or if the other direction it may be published but the change may not be saved). If either case were to happen the listeners of the events would be out of sync with the producer.

The two-phase commit can be expensive but for low latency systems there is a larger problem when dealing with this situation. Generally the queue itself is persistent so the event becomes written on disk twice in the two-phase commit, once to the Event Storage and once to the persistent queue. Given for most systems having dual writes is not that important but if you have low latency requirements it can become quite an expensive operation as it will also force seeks on the disk. Figure 5 illustrates the two-phase commit between data storage and a publishing queue.

Figure 5 Two Phase Commit with Queue

Some try to get around this problem by only writing to a queue then have something on the other side of the queue update the data storage with the changes represented by the events, this however has some issues. The largest issue is that not all of the events will be able to be written to the storage, eventual consistency has been introduced and it is possible that an optimistic concurrency problem will occur on the write of the events. Dealing with this problem in a production system is non-trivial.

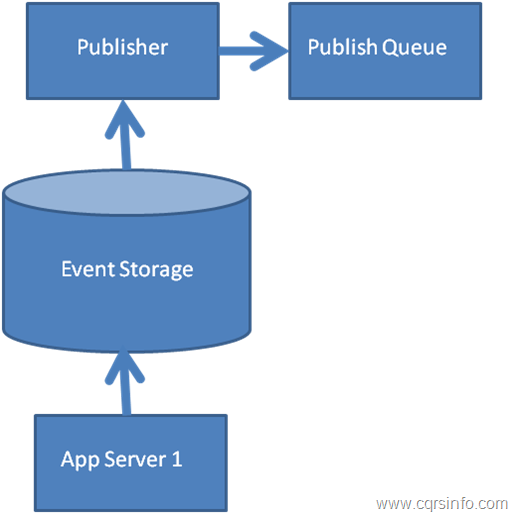

Many organizations do the opposite, use the event storage as a queue. Adding a sequence number to the Events table previously discussed allows the use the Event Storage as a queue. Figure 5 illustrates the change to the schema of the Events table.

Figure 6 Events Table as a Queue

The database would insure that the values of sequence number would be unique and incrementing, this can be easily done using an auto-incrementing type. Because the values are unique and incrementing a secondary process can chase the Events table, publishing the events off to other queue. The chasing process would simply have to store the value of the sequence number of the last event it had processed, it could even update this value with a two-phase commit bringing the update and publish to the queue into the same transaction. This process can be seen in Figure 7.

Figure 7 Event Storage as a Queue

The work has been taken off of the initial processing in a known safe way. The publish can happen asynchronously to the actual write. This lowers the latency of completing the initial operation, it also will limit the number of disk writes in the processing of the initial request to one. This strategy can be extremely valuable when dealing with low latency requirements as it allows much of the work on the initial processing to be offloaded to another process asynchronously and in a safe way, there is little difference whether the publish happens as part of the initial processing or asynchronously as generally messages are published asynchronously anyways, using the Event Store as a queue just raises the time until the message is actually published slightly, this can be viewed as slightly raising the SLA.

I have a question on using the event store as a queue. If writing to the event store is not serialized, then the sequence numbers can get out of order. And I am assuming that writing to the event store is not serialized. Let’s say a transaction writing an event with sequence number 1234 hasn’t yet committed, but the transaction for the event with sequence number 1235 has. The publisher then finds the event with sequence number 1235, publishes it, and will continue to publish events starting with 1236. If the transaction with event 1234 now commits, this event will not get published. How do you solve this?

Ramin

See Jonathans Blog post about “Out of Sequence Messages and Read Models”

http://blog.jonathanoliver.com/2011/04/cqrs-out-of-sequence-messages-and-read-models/

I have a question on the Aggregates Table, you say: “This is primarily an optimization as it could be derived from the Events table but it is much faster to query the denormalization that it would be to query the Events table directly”. When do you want to query that table? When you want to know the highest version, right? And as far as I know, that would be when you’re about to store one or more events, is there any other case?

If not, will the total time for the “store events operation” actually be faster? Do you have a number from real world data? If you have the Aggregates Table, you’ll have to “Get highest version from Aggregates Table” + “Add Events” + “Update Aggregates Table”. If you do not have it, you’ll have to “Get highest version from Events Table” + “Add Events” – there is no “Update”.

I’m fairly new to CQRS and event sourcing, and I might be missing something. But I’ve heard much talk about “Append only model” and from my understanding, this contradicts those statements..