This chapter will introduce the concept of Command and Query Responsibility Segregation. It will look at how the separation of roles in the system can lead towards a much more effective architecture. It will also analyze some of the different architectural properties that exist in systems where CQRS has been applied.

Origins

Command and Query Responsibility Segregation (CQRS) originated with Bertrand Meyer’s Command and Query Separation Principle. Wikipedia defines the principle as:

It states that every method should either be a command that performs an action, or a query that returns data to the caller, but not both. In other words, asking a question should not change the answer. More formally, methods should return a value only if they are referentially transparent and hence possess no side effects.

Wikipedia

Basically it boils down to. If you have a return value you cannot mutate state. If you mutate state your return type must be void. There can be some issues with this. Martin Fowler shows one example on the bliki with:

Meyer likes to use command-query separation absolutely, but there are exceptions. Popping a stack is a good example of a modifier that modifies state. Meyer correctly says that you can avoid having this method, but it is a useful idiom. So I prefer to follow this principle when I can, but I’m prepared to break it to get my pop.

Fowler

Command and Query Responsibility Segregation was originally considered just to be an extension of this concept. For a long time it was discussed simply as CQS at a higher level. Eventually after much confusion between the two concepts it was correctly deemed to be a different pattern.

Command and Query Responsibility Segregation uses the same definition of Commands and Queries that Meyer used and maintains the viewpoint that they should be pure. The fundamental difference is that in CQRS objects are split into two objects, one containing the Commands one containing the Queries.

The pattern although not very interesting in and of itself becomes extremely interesting when viewed from an architectural point of view.

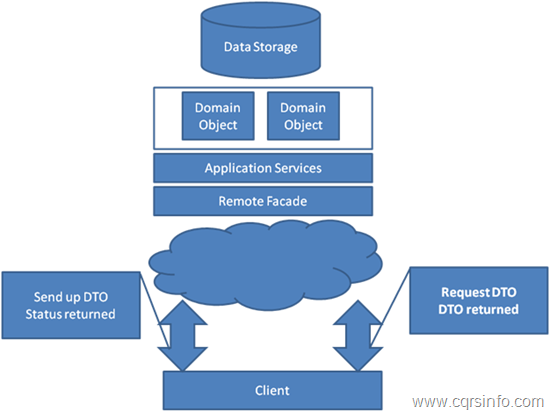

Figure 1 Stereotypical Architecture

Figure 1 contains the stereotypical architecture discussed in the first chapter. One key aspect of the architecture is that the service handles both commands and queries. More often than not the domain is also being used for both commands and queries. The application of CQRS to this architecture although quite simple in definition will drastically change architectural opportunities. A simple service to transform is in Listing 1.

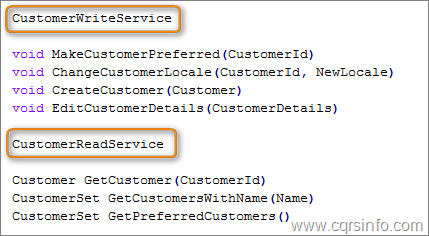

Listing 1 Original Customer Service

Applying CQRS on the CustomerService would result in two services as shown in Listing 2.

Listing 2 Customer Service after CQRS

While a relatively simple process, this will solve many of the problems that existed in the stereotypical architecture. The service has been split into two separate services, a read side and a write side or the Command side and the Query side.

This separation enforces the notion that the Command side and the Query side have very different needs. The architectural properties associated with use cases on each side are tend to be quite different. Just to name a few:

Consistency

Command: It is far easier to process transactions with consistent data than to handle all of the edge cases that eventual consistency can bring into play.

Query: Most systems can be eventually consistent on the Query side.

Data Storage

Command: The Command side being a transaction processor in a relational structure would want to store data in a normalized way, probably near 3rd Normal Form (3NF)

Query: The Query side would want data in a denormalized way to minimize the number of joins needed to get a given set of data. In a relational structure likely in 1st Normal Form (1NF)

Scalability

Command: In most systems, especially web systems, the Command side generally processes a very small number of transactions as a percentage of the whole. Scalability therefore is not always important.

Query: In most systems, especially web systems, the Query side generally processes a very large number of transactions as a percentage of the whole (often times 2 or more orders of magnitude). Scalability is most often needed for the query side.

It is not possible to create an optimal solution for searching, reporting, and processing transactions utilizing a single model.

The Query Side

As stated, the Query side will only contain the methods for getting data. From the original architecture these would be all of the methods that return DTOs that the client consumes to show on the screen.

In the original architecture the building of DTOs was handled by projecting off of domain objects. This process can lead to a lot of pain. A large source of the pain is that the DTOs are a different model than the domain and as such require a mapping.

DTOs are optimally built to match the screens of the client to prevent multiple round trips with the server. In cases with many clients it may be better to build a canonical model that all of the clients use. In either case the DTO model is very different than the domain model that was built in order to represent and process transactions.

Common smells of the problems can be found in many domains.

- Large numbers of read methods on repositories often also including paging or sorting information.

- Getters exposing the internal state of domain objects in order to build DTOs.

- Use of prefetch paths on the read use cases as they require more data to be loaded by the ORM.

- Loading of multiple aggregate roots to build a DTO causes non-optimal querying to the data model. Alternatively aggregate boundaries can be confused because of the DTO building operations

The largest smell though is that the optimization of queries is extremely difficult. Because queries are operating on an object model then being translated to a data model, likely by an ORM it can become difficult to optimize these queries. A developer needs to have intimate knowledge of the ORM and the database. The developer is dealing with a problem of Impedance Mismatch (for more discussion see “Events as a Storage Mechanism”).

After CQRS has been applied there is a natural boundary. Separate paths have been made explicit. It makes a lot of sense now to not use the domain to project DTOs. Instead it is possible to introduce a new way of projecting DTOs.

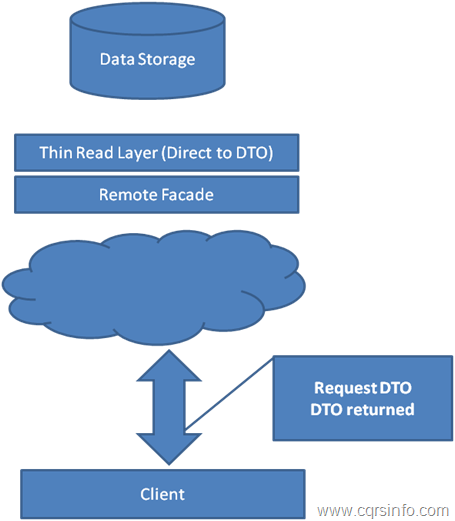

Figure 2 The Query Side

The domain has been bypassed. There is now a new concept called a “Thin Read Layer”. This layer reads directly from the database and projects DTOs. There are many ways that this can be done with handwritten ADO.NET and mapping code and a full blown ORM on the high end. Which choice is right for a team depends largely on the team itself and what they are most comfortable with. Likely the best solution is something in the middle as much of what an ORM provides is not needed and large amounts of time will be lost manually creating mapping code. A possible solution would be to use a small convention based mapping utility.

The Thin Read Layer need not be isolated from the database, it is not necessarily a bad thing to be tied to a database vendor from the read layer. It is also not necessarily bad to use stored procedures for reading, it again depends on the team and the non-functional requirements of the system.

The Thin Read Layer is not a complex piece of code although it can be tedious to maintain. One benefit of the separate read layer is that it will not suffer from an impedance mismatch. It is connected directly to the data model, this can make queries much easier to optimize. Developers working on the Query side of the system also do not need to understand the domain model nor whatever ORM tool is being used. At the simplest level they would need to understand only the data model.

The separation of the Thin Read Layer and the bypassing of the domain for reads allows also for the specialization of the domain.

The Command Side

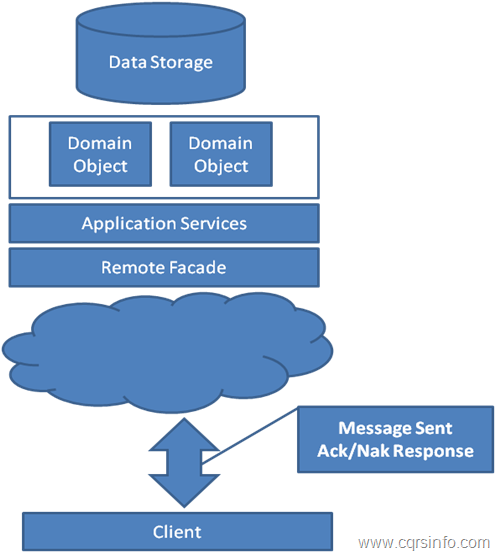

Overall the Command side remains very similar to the “Stereotypical Architecture”. The illustration in Figure 3 should look nearly identical to the previously discussed architecture. The main differences are that it now has a behavioral as opposed to a data centric contract which was needed in order actually use Domain Driven Design and it has had the reads separated out of it.

Figure 3 The Command Side

In the “Stereotypical Architecture” the domain was handling both Commands and Queries, this caused many issues within the domain itself. Some of those issues were:

- Large numbers of read methods on repositories often also including paging or sorting information.

- Getters exposing the internal state of domain objects in order to build DTOs.

- Use of prefetch paths on the read use cases as they require more data to be loaded by the ORM.

- Loading of multiple aggregates to build a DTO causes non-optimal querying to the data model. Alternatively aggregate boundaries can be confused because of the DTO building operations

Once the read layer has been separated the domain will only focus on the processing of Commands. These issues also suddenly go away. Domain objects suddenly no longer have a need to expose internal state, repositories have very few if any query methods aside from GetById, and a more behavioral focus can be had on Aggregate boundaries.

This change has been done at a lower or no cost in comparison to the original architecture. In many cases the separation will actually lower costs as the optimization of queries is simpler in the thin read layer than it would be if implemented in the domain model. The architecture also carries lower conceptual overhead when working with the domain model as the querying is separated; this can also lead towards a lower cost. In the worst case, the cost should work out to be equal; all that has really been done is the moving of a responsibility, it is feasible to even have the read side still use the domain.

By applying CQRS the concepts of Reads and Writes have been separated. It really begs the question of whether the two should exist reading the same data model or perhaps they can be treated as if they were two integrated systems, Figure 5 illustrates this concept. There are many well known integration patterns between multiple data sources in order to maintain synchronisity either in a consistent or eventually consistent fashion. The two distinct data sources allow the data models to be optimized to the task at hand. As an example the Read side can be modeled in 1NF and the transactional model could be modeled in 3nf.

The choice of integration model though is very important as translation and synchronization between models can be become a very expensive undertaking. The model that is best suited is the introduction of events, events are a well known integration pattern and offer the best mechanism for model synchronization.

Figure 4 Separated Data Models with CQRS

Common issues I come across when refactoring to CQRS. They mainly regard dealing with scenarios that are not necessarily common but require attention nevertheless to provide decent feedback to the user.

1. Exposing the consistency mismatch of the query component.

Suppose you have a CustomerWriteService and a CustomerReadService as described in the article. A call is issued to CustomerWriteService.EditCustomerDetails, then shortly thereafter, the use requests a refresh of their screen which results in a call to CustomerReadService.GetCustomer. At this point the data may not be consistent and as mentioned by several authors this issue regards the SLA not

CQRS as an architecture. However, from a practical perspective, it would be beneficial for users to become aware of this potential disparity. What are some common approaches for this?

2. Response messages for commands.

Suppose you have a CustomerWriteService as described in the article. Furthermore you have a constraint that all customer’s must have a unique email address. If you call EditCustomerDetails, where one of the detail attributes is the customer’s email address, and the processing node encounters

and duplicate email address, the attempted edit will not complete and the user should be notified somehow. In accordance with CQRS, a solution to resolve a large percentage of cases would be to call a query method before the update command is issued. However, suppose a case is encountered when an email address becomes duplicate after the check with the query component, or the query component is not yet consistent. From the perspective of the command processing node, this information can be relayed back to the client via result message. This can be achieved through a direct request / response implementation (for example using WCF dual HTTP binding), or by sending a ‘DuplicateEmailAddressEncounteredEvent’ messaga via some transport mechanism which could reference the original command. The former method conflicts with processing nodes returning void and the latter would complicate matterns on the client end, namely requiring a component to listen to events and subsequently notify the proper objects. As referenced in the article, Martin Fowler states that the former method can be used where required. I wanted to know about any existing experiences with these types of scenarios?

it is not clear at all why “Large numbers of read methods on repositories often also including paging or sorting information” was referred as a smell. cqrs magically knows about current page in a grid or about sorting order ?

another thing:

“Getters exposing the internal state of domain objects in order to build DTOs.”

what kind of internal state you afraid to expose ? what you guys trying to hide from your controllers ? 🙂

in most cases it’s simpler to just query dto and pass it through. YAGNI forever

ILIch thats exactly what CQRS does. I am confused by your comments.

As for why to hide internal domain object state: Do you write tests? Consider a domain object with a structure like:

InventoryItem

decimal Price

string Name

decimal Weight

bool Activated

with a behaviour of Deactivate()

When I write a unit test that calls Deactivate, if I expose state I would need to test that it does *not* change price/name/weight no (is it more important to test what we expect to have happened happened or what we didnt expect to have happen didnt happen)? This quickly becomes an exponential nightmare.

thank you for your response ! I think i got your point.

I’m following yagni and trying not to create dtos when they are not strongly required.

I’m writing tests only for critical parts of the system and they are not superdetailed, cause my architecture needs to flexible but tests make it more fragile. Also we have lack of resources (startup)