Most systems in production today rely on the storing of current state in order to process transactions. In fact it is rare to meet a developer who has worked on a system that maintains current state in any other way. It has not always been like this.

Before the general acceptance of the RDBMS as the center of the architecture many systems did not store current state. This was especially true in high performance, mission critical, and/or highly secure systems. In fact if we look at the inner workings of a RDBMS we will find that most RDBMSs themselves not actually work by managing current state!

The goal of this section is to introduce the concept of event sourcing, to show the benefits, to show how a simple event storage system can be created utilizing a Relational Database for underlying data management.

What is a Domain Event?

An event is something that has happened in the past.

All events should be represented as verbs in the pas t tense such as CustomerRelocated, CargoShipped, or InventoryLossageRecorded. For those who speak French, it should be in Passé Composé, they are things that have completed in the past. There are interesting examples in the English language where it is tempting to use nouns as opposed to verbs in the past tense, an example of this would be “Earthquake” or “Capsize”, as a congressman recently worried about Guam, but avoid the temptation to use names like this and stick with the usage of verbs in the past tense when creating Domain Events.

It is absolutely imperative that events always be verbs in the past tense as they are part of the Ubiquitous Language. Consider the differences in the Ubiquitous Language when we discuss the side effects from relocating a customer, the event makes the concept explicit where as previously the changes that would occur within an aggregate or between multiple aggregates were left as an implicit concept that needed to be explored and defined. As an example, in most systems the fact that a side effect occurred is simply found by a tool such as Hibernate or Entity Framework, if there is a change to the side effects of a use case, it is an implicit concept. The introduction of the event makes the concept explicit and part of the Ubiquitous Language; relocating a customer does not just change some stuff, relocating a customer produces a CustomerRelocatedEvent which is explicitly defined within the language.

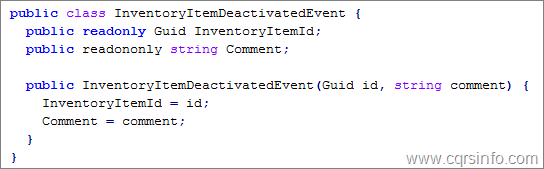

In terms of code, an event is simply a data holding structure as can be seen in Listing 1.

Listing 1 A Simple Event

The code listing looks very similar to the code listing that was provided for a Command. The main differences exist in terms of significance and intent. Commands have an intent of asking the system to perform an operation where as events are a recording of the action that occurred.

Other Definitions and Discussion

There is a related concept to a Domain Event in this description that is defined in Streamlined Object Modeling (SOM). Many people use the term “Domain Event” In SOM when discussing “The Event Principle”

Model the event of people interacting at a place with a thing with a transaction object. Model a point-in-time interaction as a transaction with a single timestamp; model a time-interval interaction as a transaction with multiple timestamps.

Jill Nicola, 2002ll, p. 23

Although many people use the terminology of a Domain Event to describe this concept the terminology is not having the same definition as a Domain Event in the context of this document. SOM uses another terminology for the concept that better describes what the object is, a Transaction. The concept of a transaction object is an important one in a domain and absolutely deserves to have a name. An example of such a transaction might be a player swinging a bat, this is an action that occurred at a given point in time and should be modeled as such in the domain, this is not however the same as a Domain Event.

This also differs from Martin Fowler’s example of what a Domain Event is.

“Example: I go to Babur’s for a meal on Tuesday, and pay by credit card. This might be modeled as an event, whose type is “Make Purchase”, whose subject is my credit card, and whose occurred date is Tuesday. If Babur’s uses and old manual system and doesn’t transmit the transaction until Friday, then the noticed date would be Friday.”

Fowler

Further along

“By funneling inputs of a system into streams of Domain Events you can keep a record of all the inputs to a system. This helps you to organize your processing logic, and also allows you to keep an audit log of the system”

(Fowler

The astute reader may pick up that what Martin is actually describing here is a Command as was discussed previously when discussing Task Based UIs. The language of “Make Purchase” is wrong. A purchase was made. It makes far more sense to introduce a PurchaseMade event. Martin did actually make a purchase at the location, they did actually charge his credit card, and he likely ate and enjoyed his food. All of these things are in the past tense, they have already happened and cannot be undone.

An example such as the sales example given also tends to lead towards a secondary problem when built within a system. The problem is that the domain may be responsible for filling in parts of the event. Consider a system where the sale is processed by the domain itself, how much is the sales tax? Often the domain would be calculating this as part of its calculations. This leads to a dual definition of the event, there is the event as is sent from the client without the sales tax then the domain would receive that and add in the sales tax, it causes the event to have multiple definitions, as well as forcing mutability on some attributes. Dual events can sidestep this issue (one for the client with just what it provides and another for the domain including what it has enriched the event from the client with) but this is basically the command event model and the linguistic problems still exist.

A further example of the linguistic problems involved can be shown in error conditions. How should the domain handle the fact that a client told it to do something that it cannot? This condition can exist for many reasons but let’s imagine a simple one of the client simply not having enough information to be able to source the event in a known correct way. Linguistically the command/event separation makes much more sense here as the command arrives in the imperative “Place Sale” while the event is in the past tense “SaleCompleted”. It is quite natural for the domain to reject a client attempting to “Place a sale”; it is not natural for the domain to tell the client that something in the past tense no longer happened. Consider the discussion with a domain expert; does the domain have a time machine? Parallel realities are far too complex and costly to model in most business systems.

These are exactly the problems that have led to the separation of the concepts of Commands and Events. This separation makes the language much clearer and although subtle it tends to lead developers towards a clearer understanding of context based solely on the language being used. Dual definitions of a concept force the developer to recognize and distinguish context, this weight can translate into both ramp up time for new developers on a project and another thing a member of the team needs to “remember”. Anytime a team member needs to remember something to distinguish context there is a higher probability that it will be overlooked or mistook for another context. Being explicit in the language and avoiding dual definitions helps make things clearer both for domain experts, the developers, and anyone who may be consuming the API.

Events as a Mechanism for Storage

When most people consider storage for an object they tend to think about it in a structural sense. That is when considering how the “sale” discussed above should be stored they think about it as being stored as a “Sale” that has “Line Items” and perhaps some “Shipping Information” associated with it. This is not however the only way that the problem can be conceptualized and other solutions offer different and often interesting architectural properties.

Consider for a moment the creation of a small Order object for a web based sale system. Most developers would envision something similar to what is represented in Figure 1. That is a structural viewpoint of what the Order is. An Order has n Line Items and Shipping Information. Of course this is an overly simplified view of what an Order is but it can be seen that the focus is upon the structure of the order and its parts.

Figure 1 A Structural View of an Order

This is not the only way that this data can be viewed. Previously in the area of discussions there was a discussion about the concept of a transaction. Developers deal with the concept of transactions regularly, they can be viewed as representing the change between a point and the next subsequent point. They are also regularly called “Deltas”. The delta is between two static states can always be defined but more often than not this is left to be an implicit concept, usually relegated to a framework such as Hibernate in the Java world or Entity Framework in the Microsoft world. These frameworks save the original state and then calculate the differences with the new state and update the backing data model accordingly. The making of these deltas explicit can be highly valuable both in terms of technical benefits and more importantly in business benefits.

The usage of such deltas can be seen in many mature business models. The canonical example of delta usage is in the field of accounting. When looking at a ledger such as in Figure 2 each transaction or delta is being recorded. Next to it is a denormalized total of the state of the account at the end of that delta. In order to calculate this number the current delta is applied to the last known value. The last known value can be trusted because at any given point the transactions from the “beginning of time” for that account could be re-run in order to reconcile the validity of that value. In there exists a verifiable audit log.

Figure 2 A Simplified Ledger

Because all of the transactions or deltas associated with the account exist, they can be stepped through verifying the reult. The “Current Balance” at any point can be derived either by looking at the “Current Balance” or by adding up all of the “Changes” since the beginning of time for the account. The second property is obviously valuable in a domain such as accounting as accountants are dealing with money and the ability to check that calculations were performed correctly is extremely valuable, it was even more valuable before computers when it was common place to have an exhausted accountant make a mistake in a calculation at 3 am when they should be sleeping instead of working with the books.

There are however some other interesting properties to this mechanism of representing state, as an example, it is possible to go back and look at what a state was at a given point in time. Consider for that the account was allowed to reach a balance of below zero and there is a rule that says it is not supposed to. It is possible and relatively easy, to view the account as it was just prior to processing that transaction that put it into the invalid state and see what state it was in, making it far easier to reproduce what often times end up as heisenbugs in other circumstances.

These types of benefits are not only limited to naturally transaction based domains though. In fact every domain is a naturally transaction based domain when Domain Driven Design is being applied. When applying Domain Driven Design there is a heavy focus on behaviors, normally coinciding with use cases, Domain Driven Design is interested in how users use the system.

Returning to the Order example from Figure 1, the same order could be represented in the form of a transactional model as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Transactional View of Order

This can be applied to any type of object. By replaying through the events the object can be returned to the last known state. It is mathematically equivalent to store the end of the equation or the equation that represents it. There is a structural representation of the object, but it exists only by replaying previous transactions to return the structure to its last known state, data is not persisted in a structure but as a series of transactions. One very interesting possibility here is that unlike when storing current state in a structural way there is no coupling between the representation of current state in the domain and in storage, the representation of current state in the domain can vary without thought of the persistence mechanism.

It is vitally important to note the language in Figure 3. All of the verbs are in the past tense. These are Domain Events. Consider what would happen if the language were in the imperative tense, “Add 2 socks item 137”, “Create Cart”. What if there were behaviors associated with adding and item (such as reserving it from an inventory system via a webservice call), should these behaviors be when reconstituting an object? What if logic has changed so that this item could no longer be added given the context? This is one of many examples where dual contexts between Commands and Events are required, there is a contextual difference between returning to a given state and attempting to transition to a new one.

There is no Delete

A common question that arises is how to delete information. It is not possible as previously jump into the time machine and say that an event never happened (eg: delete a previous event). As such it is necessary to model a delete explicitly as a new transaction as shown in Figure 4. Further discussion on the business value of handling deletes in this mechanism can be found in “Business Value of the Event Log”.

Figure 4 Transactional View of Order with Delete

In the event stream in Figure 4 the two pairs of socks were added then later removed. The end state is equivalent to not having added the two pairs of socks. The data has not however been deleted, new data has been added to bring the object to the state as if the first event had not happened, this process is known as a Reversal Transaction.

By placing a Reversal Transaction in the event stream not is the object returned to the state as if the item had not been added, the reversal leaves a trail that shows that the object had been in that state at a given point in time.

There are also architectural benefits to not deleting data. The storage system becomes an additive only architecture, it is well known that append-only architectures distribute more easily than updating architectures because there are far fewer locks to deal with.

Performance and Scalability

As an append-only model storing events is a far easier model to scale. There is however other benefits in terms of performance and scalability especially compared with a stereotypical relational model. As an example, the storage of events offers a much simpler mechanism to optimize as it is limited to a single append-only model. There are many other benefits.

Partitioning

A very common performance optimization in today’s systems is the use of Horizontal Partitioning. With Horizontal Partitioning the same schema will exist in many places and some key within the data will be used to determine in which of the places the data will exist. Some have renamed the term to “Sharding” as of late. The basic idea is that you can maintain the same schema in multiple places and based on the key of a given row place it in one of many partitions.

One problem when attempting to use Horizontal Partitioning with a Relational Database it is necessary to define the key with which the partitioning should operate. This problem goes away when using events. Aggregate IDs are the only partition point in the system. No matter how many aggregates exist or how they may change structures, the Aggregate Id associated with events is the only partition point in the system.

Horizontally Partitioning an Event Store is a very simple process.

Saving Objects

When dealing with a stereotypical system utilizing a relational data storage it can be quite complex to figure out what has changed within the Aggregate. Again many tools have been built to help alleviate the pain that arises from this often complex task but is the need for a tool a sign of a bigger problem?

Most ORMs can figure out the changes that have occurred within a graph. They do this generally by maintaining two copies of a given graph, the first they hold in memory and the second they allow other code to interact with. When it becomes time to save a complex bit of code is run, walking the graph the code has interacted with and using the copy of the original graph to determine what has changed while the graph was in use by the code. These changes will then be saved back to the data storage system.

In a system that is Domain Event centric, the aggregates are themselves tracking strong events as to what has changed within them. There is no complex process for comparing to another copy of a graph, instead simply ask the aggregate for its changes. The operation to ask for changes is far more efficient than having to figure out what has changed.

Loading Objects

A similar issue exists when loading objects. Consider the work that is involved with loading a graph of objects in a stereotypical relational database backed system. Very often there are many queries that must be issued to build the aggregate. In order to help minimize the latency cost of these queries many ORMs have introduced a heuristic of Lazy Loading also known as Delayed Loading where a proxy is given in lieu of the real object. The data is only loaded when some code attempts to use that particular object.

Lazy Loading is useful because quite often a given behavior will only use a certain portion of data out of the aggregate and it prevents the developer from having to explicitly represent which data that is while amortizing the cost of the loading of the aggregate. It is this need for amortization of cost that shows a problem.

Aggregates are considered as a whole represented by the Aggregate Root. Conceptually an Aggregate is loaded and saved in its entirety.

Evans, 2001.

Conceptually it is much easier to deal with the concept of an Aggregate being loaded and saved in its entirety. The concept of Lazy Loading is not a trivial one when added and is especially not trivial when optimizing use cases. The heuristic is needed because loading full aggregates from a relational database is operationally too slow.

When dealing with events as a storage mechanism things are quite different. There is but one thing being stored, events. Simply load all of the events for an Aggregate and replay them. There can only ever be a single query on the system, there is no need to attempt to implement things like Lazy Loading. This is bad for people who want to build complex and quite often impressive frameworks for managing things like Lazy Loading but it is good for development teams who no longer need to learn these frameworks.

Many would quickly point out that although it requires more queries in a relational system, when storing events there may be a huge number of events for some aggregates. This can happen quite often and a relatively simple solution exists for the problem.

Rolling Snapshots

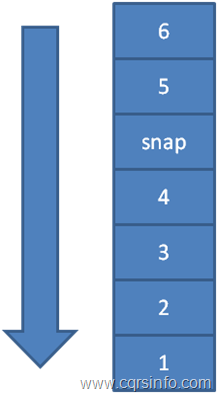

A Rolling Snapshot is a denormalization of the current state of an aggregate at a given point in time. It represents the state when all events to that point in time have been replayed. Rolling Snapshots are used as a heuristic to prevent the need to load all events for the entire history of an aggregate. Figure 5 shows a typical Event Stream. One way of process thing the event stream is to replay the events from the beginning of time until the end of the event stream is reached.

Figure 5 An Event Stream

The problem that exists is that there may be a very large number of events between the beginning of time and the current point. It can be easily imagined that there is an event stream with a million or more events that have occurred, such an event stream would be quite inefficient to load.

The solution is to use a Rolling Snapshot, to place a denormalization of the state at a given point in time. It would then be possible to only play the events from that point in time forward in order to load the Aggregate.

Figure 6 Event Stream with Snapshot

Figure 6 shows an Event Stream with a Rolling Snapshot placed within it. The process for rebuilding an Aggregate changes when using Rolling Snapshots. Instead of reading from the beginning of time forward, it is read backwards putting the events on to a stack until either there were no more events left or a snapshot was found. The snapshot would then if found be applied and the events would be popped off the stack and applied until the stack was empty.

It is important to note that although this is an easy way to conceptualize how Rolling Snapshots work, that this is a less than ideal solution in a production system for various reasons. Further discussion on the implementation of Rolling Snapshots can be found in “Building an Event Storage”.

The snapshot itself is nothing more than a serialized form of the graph at that given point in time. By having the state of that graph at that point in time replaying all the events prior to that snapshot can be avoided. Snapshots can be taken asynchronously by a process monitoring the Event Store.

Introducing Rolling Snapshots allows control of the worst case when loading from events. The maximum number of events that would be processed can be tuned to optimize performance for the system in question. With the introduction of Rolling Snapshots it is a relatively trivial process to achieve one to two orders of magnitude of performance gain on the two operations that the Event Storage supports. It is important though to remember that Rolling Snapshots are just a heuristic and that conceptually the event stream is still viewed in its entirety.

Impedance Mismatch

Using events as a storage mechanism also offers very different properties when compared to a typical relational model when the impedance mismatch that exists between a typical relational model and the object oriented domain model is analyzed. Scott Ambler describes the problem in an essay on agiledata.org as

“Why does this impedance mismatch exist? The object-oriented paradigm is based on proven software engineering principles. The relational paradigm, however, is based on proven mathematical principles. Because the underlying paradigms are different the two technologies do not work together seamlessly. The impedance mismatch becomes apparent when you look at the preferred approach to access: With the object paradigm you traverse objects via their relationships whereas with the relational paradigm you join the data rows of tables. This fundamental difference results in a non-ideal combination of object and relational technologies, although when have you ever used two different things together without a few hitches?”

Ambler

The impedance mismatch between the domain model and the relational database has a large cost associated with it. There are many tools that aim to help minimize the effects of the impedance mismatch such as Object Relational Mappers (ORM). They tend to work well in most situations but there is still a fairly large cost associated to the impedance mismatch even when using tools such as ORMs.

The cost is that a developer really needs to be intimately with both the relational model and the object oriented model. They also need to be familiar with the many subtle differences between the two models. Scott identifies this with

“To succeed using objects and relational databases together you need to understand both paradigms, and their differences, and then make intelligent tradeoffs based on that knowledge.”

Ambler

Some of these subtle differences can be found in Wikipedia under the “Object-Relational Impedance Mismatch” page but to include some of the major differences.

Declarative vs. imperative interfaces — Relational thinking tends to use data as interfaces, not behavior as interfaces. It thus has a declarative tilt in design philosophy in contrast to OO’s behavioral tilt. (Some relational proponents propose using triggers, stored procedures, etc. to provide complex behavior, but this is not a common viewpoint.)

Object-Relational Impedance Mismatch

Structure vs. behaviour — OO primarily focuses on ensuring that the structure of the program is reasonable (maintainable, understandable, extensible, reusable, safe), whereas relational systems focus on what kind of behaviour the resulting run-time system has (efficiency, adaptability, fault-tolerance, liveness, logical integrity, etc.). Object-oriented methods generally assume that the primary user of the object-oriented code and its interfaces are the application developers. In relational systems, the end-users’ view of the behaviour of the system is sometimes considered to be more important. However, relational queries and "views" are common techniques to re-represent information in application- or task-specific configurations. Further, relational does not prohibit local or application-specific structures or tables from being created, although many common development tools do not directly provide such a feature, assuming objects will be used instead. This makes it difficult to know whether the stated non-developer perspective of relational is inherent to relational, or merely a product of current practice and tool implementation assumptions.

Object-Relational Impedance Mismatch

Set vs. graph relationships – The relationship between different items (objects or records) tend to be handled differently between the paradigms. Relational relationships are usually based on idioms taken from set theory, while object relationships lean toward idioms adopted from graph theory (including trees). While each can represent the same information as the other, the approaches they provide to access and manage information differ.

Object-Relational Impedance Mismatch

There are many other subtle differences such as data types, identity, and how transactions work. The object-relational impedance mismatch can be quite a pain to deal with and it requires a very large amount of knowledge to deal with effectively.

There is not an impedance mismatch between events and the domain model. The events are themselves a domain concept, the idea of replaying events to reach a given state is also a domain concept. The entire system becomes defined in domain terms. Defining everything in domain terms not only lowers the amount of knowledge that developers need to have, it also limits the number of representations of the model needed as the events are directly tied to the domain model itself.

Business Value of the Event Log

It needs to be made clear at the very start of this section that the value of the Event Log is directly correlated with places that you would want to use Domain Driven Design in the first place. Domain Driven Design should be used in places where the business derives competitive advantage. Domain Driven Design itself is very difficult and expensive to apply; a company will however receive high ROI on the effort if the domain is complex and if they derive competitive advantage from it. Using an Event Log similarly will have high ROI when dealing with an area of competitive advantage but may have negative ROI in other places.

Storing only current state only allows to ask certain kinds of questions of the data. For example consider orders in the stock market. They can change for a few reasons, an order can change the amount of volume that they would like to buy/sell, the trading system can automatically adjust the volume of an order, or a trade could occur lowering the volume available on the current order.

If posed with a question regarding current liquidity such as the price for a given number of shares in the market, it really does not matter which of these changes occurred, it does not really matter how the data got the way it was, it matters what it is at a given point in time. A vast majority of queries even in the business world are focused on the what, labels to send customers mails, how much was sold in April, how many widgets are in the warehouse.

There are however other types of queries that are becoming more and more popular in business, they focus on the how. Examples can commonly be seen in the buzzword “Business Intelligence”. Perhaps there is a correlation between people having done an action and their likelyhood of purchasing some product? These types of questions generally focus on how something came into being as opposed to what it came out to be.

It is best to go through an example. There is a development team at a large online retailer. In an iteration planning meeting a domain expert comes up with an idea. He believes that there is a correlation between people having added then removed an item from their cart and their likelihood of responding to suggestions of that product by purchasing it at a later point. The feature is added to the following iteration.

The first hypothetical team is utilizing a stereotypical current state based mechanism for storing state. They plan that in this iteration they will add tracking of items via a fact table that are removed from carts. They plan for the next iteration that they will then build a report. The business will receive after the second iteration a report that can show them information back to the previous iteration when the team released the functionality that began tracking items being removed from carts.

This is a very stereotypical process, at some organizations the report and the tracking may be released simultaneously but this is a relatively small detail in the handling. From a business perspective the domain experts are happy, they made a request of the team and the team was able to quickly fulfill the request, new functionality has been added in a quick and relatively painless way. The second team will however have quite a different result.

The second team has been storing events; they represent their current state by building up off of a series of events. They just like the first team go through and add tracking of items removed from carts via a fact table but they also run this handler from the beginning of the event log to back populate all of the data from the time that the business started. They release the report in the same iteration and the report has data that dates back for years.

The second team can do this because they have managed to store what the system actually did as opposed to what the current state of data is. It is possible to go back and look and interpret the old data in new and interesting ways. It was never considered to track what items were removed from carts or perhaps the number of times a user removes and items from their cart was considered important. These are both examples of new and interesting ways of looking at data.

As the events represent every action the system has undertaken any possible model describing the system can be built from the events.

Businesses regularly come up with new and interesting ways of looking at data. It is not possible with any level of confidence to predict how a business will want to look at today’s data in five years. The ability for the business to look at the data in the way that it wants in five years is of an unknown but possibly extremely high value; it has already been stated that this should be done in areas where the business derives its competitive advantage so it is relatively easy to reason that the ability to look at today’s data in an unexpected way could be a competitive advantage for the business. How do you value the possible success or failure of a company based upon an architectural decision now?

How do software teams justify looking at their Magic 8 Ball to predict what the business will need in five or even ten years? Many try to use YAGNI (You Ain’t Gonna Need It) (Wikipedia) but YAGNI only applies when you actually know that you won’t need it, how can the dynamic world of business and how they may want to look at data in five or ten years be predicted?

- Is it more expensive to actually model every behavior in the system? Yes.

- Is it more expensive in terms of disk cost and thought process to store every event in the system? Yes.

- Are these costs worth the ROI when the business derives a competitive advantage from the data?

Works Cited

- Ambler, S. W. (n.d.). The Object Relational Mismatch. Retrieved from agiledata.org: http://www.agiledata.org/essays/impedanceMismatch.html

- Evans, E. (2001). Domain Driven Design. Addisson Wesley.

- Fowler, M. (n.d.). Domain Event. Retrieved from EAA Dev: http://martinfowler.com/eeaDev/DomainEvent.html

- Jill Nicola, M. M. (2002ll). Streamlined Object Modelling. Prentice H.

- Object-Relational Impedance Mismatch. (n.d.). Retrieved from Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Object-relational_impedance_mismatch

- Wikipedia. (n.d.). You ain’t gonna need it. Retrieved from wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/You_ain’t_gonna_need_it

Very interesting concept. Thank you for aggregating and bundling this complex subject in such an easily approachable and understandable way.